Link to audio from presentation and questions from Committee.

Good afternoon, and thank you for the opportunity to speak.

My name is Morgane Oger. I am a licensed commercial mariner, founding director of the Morgane Oger Foundation, and a member of the BC Nautical Residents Association.

I am the owner and master of SENA II, a commercial vessel active in British Columbia. I am also manager of data platforms and data operations for a national multichannel retailer.

I’m here today to ask the Province to include in its next budget a $100,000 one-year study and a $1 million pilot program to help address the affordability crisis by supporting infrastructure that helps British Columbians live full-time on their vessels as an alternative to the traditional housing supply.

The per-unit cost of new housing supported through this small investment will be a fraction of the cost of building new traditional housing.

In addition, it will help increase resilience for residents who are already living on vessels by legitimizing their housing choices and including them in provincial planning and support structures.

This small investment will make living on a vessel more attractive, and will relieve pressure on land-based housing.

It will also bring fairness to an overlooked population of British Columbians and help stimulate remote coastal communities.

British Columbia’s affordability crisis touches almost everyone, but it doesn’t impact us all to the same extent.

I will briefly look at four real households to show just how unequal the experience of affordability can be—and why modest support for non-traditional housing such as liveaboards can make a meaningful difference for many.

Household One: The Resilient Retirees

A retired household in their 80s. They own their home outright in Vancouver and live on a stable, indexed income thanks to their pensions and savings.

They’ve carefully tracked food costs for over a decade. A kilo of sirloin steak they bought for $16 in 2011 now costs over $60.

Their grocery basket has quadrupled in cost. For them, inflation is frustrating—but not catastrophic. They are largely protected from changing costs of housing by asset ownership and institutional stability.

Household Two: The Professionally-Employed Liveaboard

I live aboard a commercial fishing vessel, on which I work remotely, managing a high tech team, and support two children as they start out their in university journeys.

My fixed monthly costs are low—about $2,000. However on a boat I am responsible for every part of my infrastructure:

Sewage treatment and garbage disposal treatment, recycling, electricity, safety, and mooring.

Many boaters are not professionals with high income.

They turned to the water to escape unaffordable rents, inaccessible housing, or unsafe shelters.

They are housed—but invisible in provincial and municipal policy.

We receive no CleanBC rebates, no tenancy protections – all because many provicial programs are tied to home ownership or rental.

In many municipalities, we face bylaws designed to displace us. The Province has no count of us—yet we exist in the thousands.

Household Three: The Precarious Middle Class

A couple made up of one public school teacher married to someone who had to change careers due to disability induced by an injury travelling to work.

They own their suburban home, financed through a variable-rate line of credit now covering half its value. Their two young adult children are just entering post-secondary education. Like many British Columbians, they are neither poor nor secure. A single job loss or rate hike could collapse their household budget.

Their children, like mine and many others, tell us they worry they see no future in BC because housing is so unaffordable.

Household Four: The Vulnerable Senior

A person living alone who recently turned 65. After two decades on provincial disability assistance, they now rely on CPP and OAS. They live in subsidized housing under a BC Housing subsisy with little financial resilience.

When ground beef jumps from $8 to $22 a kilo, the choice becomes: eat less, or eat worse. They are one of hundreds of thousands in BC living with a disability—many who live with food insecurity.

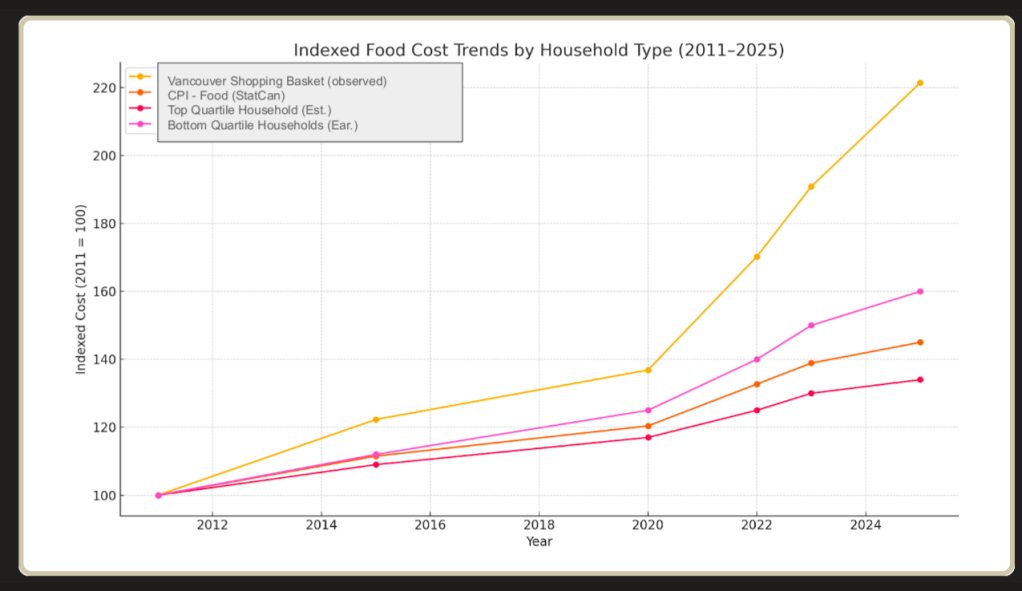

Household One tracked their grocery costs over the last 20 years. The food cost data they collected shows just how misleading official inflation metrics can be. While the Consumer Price Index reports a 45% rise in food prices from 2011 to today, their grocery basket cost has more than tripled. The CPI doesn’t reflect how low-income households can’t substitute goods, stockpile, or absorb price shocks. Inflation for them is a nutritional crisis, not just a budgetary one.

People in BC are struggling and every measure to reduce unaffordability can help. Housing is one place where creativity could yield disproportionate benefits.

So what can the Province do?

Affordability strategies could take into consideration people who housed in non-traditional housing – or who are willing to while the province ensures the housing stock is built up. Thousands of people could be living on boats at marina or travelling throughout BC waters and freeing up the rental market.

All it would take is small inexpensive infrastructure improvements and some minor policy change.

And the Province would be able to house more households for less money than it does today.

Policy Proposal: The Liveaboard Infrastructure Pilot

I propose a $1.1 million pilot program to bring liveaboards into BC’s housing strategy. It includes:

- $100,000 for a provincial study to map the liveaboard population, needs, and opportunities

- $1 million in matching funds for municipalities and First Nations to improve infrastructure: dinghy docks, breakwater improvements, utilities, and pump-out services

- Sewage treatment incentives to encourage adoption of certified marine sanitation devices on veasels to address pollution concerns.

- Lease-based requirements for marinas on provincial water lots to support designated liveaboard capacity

This isn’t about luxury yachts.

It’s about enabling low-impact, self-managed housing that already exists that some people want to access but is excluded from policy and planning.

The cost of the program or of infrastructure could be recuperated through a participation fee for liveaboards wishing to access infrastructure. For example, a liveaboard licensing system.

Conclusion: One Province, Many Realities

These four households—all real—show the diverse ways British Columbians experience housing and affordability.

By modestly investing in a sustainable, self-funded housing solution, the Province can ease rental pressure, support climate goals, and serve people who are already helping themselves.

Let’s pilot a better way forward.

Thank you.

Morgane Oger, Master – SENA II

Email: m.oger@roitaystems.ca

Leave a reply to Brent Swain Cancel reply